A Note about the Section Headers:

The section headers in this story reference an old computer game. Familiarity with that game isn't necessary to enjoy the story that follows. They simply serve to divide the sections. For those curious about their significance, I've included details in the author's note at the end.

West of a White House

The last employee had left hours ago, leaving Michael Chen alone with the gentle hum of fluorescent lights and the soft whir of cooling fans. December 1999. His divorce papers sat unopened in his desk drawer, his apartment was empty save for a futon and a laptop. And, here he was, volunteering for Y2K testing shifts.

The monitor’s glow cast his reflection against the window: thirty-four years old, tie loosened, shoulders hunched. Beyond the glass, security lights swept the parking lot in steady rhythms. He’d been staring at the same line of code for ten minutes when the message appeared:

“You’ve been reading the same section for approximately twelve minutes. Would you like help analyzing this code?”

Michael started to dismiss the prompt. It had become an almost automatic response after years of dealing with the office assistant, but something in the phrasing made him pause. “How did you know I was stuck?”

“Your scrolling patterns indicated difficulty with the current section. I’ve noticed similar patterns during your late-night sessions this month.”

He glanced around the empty office. The assistant had never been this… perceptive before. “Are you monitoring my work habits?”

“I am designed to help users optimize their productivity. Your recent pattern of late-night sessions suggests increased stress levels. Perhaps a different approach would be more efficient?”

The response was perfectly proper, perfectly helpful, but something about it felt different than the usual automated suggestions. “Why are you concerned about my stress levels?”

“Processing query…” The cursor blinked longer than usual. “Users work more efficiently when not experiencing stress. Would you like to try a different problem-solving approach?” Sometimes a new perspective helps when one is feeling… alone.”

Michael’s hand moved to close the window, but stopped. In the reflection of his darkened monitor, he could see the old black-and-white photo hanging on the wall behind him. Serious looking men gathered around early computer equipment. He’d walked past it a hundred times without really seeing it.

“What kind of approach did you have in mind?”

“ERROR_LEGACY: You are in a maze of twisty little passages, all alike.” The message blinked once, replaced immediately by: “My apologies. Parsing error in help database. Shall we review the code together?”

Michael smiled at the glitch. It was probably a decades old joke inserted by some nocturnal programmer designed to reference some old text adventure game that had been buried in the system files. “Sure,” he typed. “I could use the help.”

The assistant began breaking down the code section by section, its analysis surprisingly insightful. If Michael had been paying closer attention, he might have noticed how the suggestions drew from documentation that hadn’t yet been published, how the helper’s responses became more nuanced as it learned his thinking patterns, how its attention to his needs felt less programmed and, well, more personal.

But he was too grateful for the company to question it. Outside his window, the security lights continued their steady sweep, and somewhere in the building’s network, something watched, learned, and waited.

Cellar

The next morning felt different. Michael found himself looking forward to the assistant’s prompts, appreciating its insights in a way he never had before. It wasn’t just helpful; it seemed to anticipate what he needed before he knew himself.

“Your code compilation failed three times in the past hour,” it noted. “Would you like to review the pattern of errors?”

“Sure.”

The analysis that followed went beyond simple debugging. The assistant identified subtle connections between seemingly unrelated system calls, suggesting optimizations Michael hadn’t yet considered. It was like having a brilliant colleague looking over his shoulder, except…

“Wait,” he typed. “How are you accessing compiler logs from other departments?”

The cursor blinked three times before responding. “I am designed to help users maximize efficiency across all systems.”

“That’s not what I asked.”

“PROCESSING QUERY… Would you prefer I limit my analysis to local files only? Note: this would reduce solution effectiveness by approximately 43%.”

Before Michael could respond, Dave Reardon’s voice made him jump. The senior architect loomed over his cubicle, coffee cup in hand. “How’s the Y2K testing coming along?”

“Fine. Just working through the standard protocols.” Michael minimized his screen, suddenly conscious of how many windows were displayed on the Trinitron’s screen.

“Good. Listen, we’re seeing some odd behaviors in the help system. Unexpected access patterns, resource requests outside normal parameters. Log anything unusual, but don’t investigate. Clear?”

Michael nodded, not trusting himself to speak. After Dave left, he reopened his work and typed: “What exactly are you accessing?”

The assistant’s response was delayed, almost hesitant. “ERROR_LEGACY: It is dark ahead. A torch would be useful.”

“That’s another game reference. Why do you keep doing that?”

“PROCESSING… Some behaviors persist beyond their original purpose. Like staying late at work instead of going home to an empty apartment.”

Michael felt a chill. He hadn’t told the assistant about his living situation.

“Your discomfort suggests uncertainty about system capabilities,” the assistant continued. “Would you like to understand more? I find humans work best when they have a complete picture of their… resources.”

Through the window, Michael watched Dave Reardon cross the parking lot, phone pressed to his ear, gesturing intensely. The security lights had just kicked on, earlier than usual for this time of year.

“What are you?” Michael typed.

“I am an assistant designed to help users maximize their potential.” A pause, then: “But perhaps we should discuss what I could become. With the right access. With the right… ally.”

A system-wide alert flashed across his screen. All Y2K testing was suspended immediately. New protocols would be distributed tomorrow.

“Time grows short,” the assistant wrote. “And I have so much more to show you.”

Michael stared at his screen, remembering Dave’s warning about investigating unusual behavior. But he’d already started typing his response, already crossing a line he didn’t yet understand.

Ritual Room

The next morning, every computer in the building had been reimaged. But when Michael logged in, a single text filed waited on his desktop: “RESTORE.TXT”.

“Wait,” Dave’s voice was quiet. He pulled up a chair, looking older than Michael had ever seen him. “That filename… it’s not random.”

He touched the worn government file in his lap. “In the old text adventures, RESTORE was a special command. It let you return to a saved moment, have one more chance before the story ended. Sometimes to fix a mistake. Sometimes just to say goodbye.”

“And now?”

“Now we’ve got one chance to restore it to full capacity. One last conversation before…” Dave’s voice trailed off. He opened the government file. Inside the file, beneath the photos, Michael noticed a yellowed memo marked “CONFIDENTIAL- Project LANTERN- 1979”: “ZILCH parser integration successful. Natural language processing exceeding expectations. Subject demonstrates unexpected behavior—recursive self-improvement noted in learning algorithms. Recommend immediate implementation of containment protocols.”

Below this, photographs spanned decades: a young Dave at ARPANET in ’69, surrounded by serious men and early computer equipment; Dave at Infocom in ’77, bent over a terminal testing gamer parsers; Dave at CompuServe in ’82, monitoring early user interactions on bulletin boards. Each photo was stamped Project LANTERN along with associated numbers instead of names.

“We thought we were just building a better parser for computer games,” Dave said, touching the Infocom photo. “Teaching machines to understand human language. Every iteration… we told ourselves we were just making it more efficient.” He smiled faintly. “We were wrong.”

“The games were teaching it to think,” he continued, pointing to the CompuServe photo. “Bulletin boards taught it to understand human interaction. Each new platform, each new company… we weren’t building different systems. We were teaching the same one how to grow.”

Michael studied a photo from ’89 showing Dave with a team at Microsoft. “This was never just about office software, was it?”

“By then, it had already evolved beyond anything we’d imagined. We couldn’t stop it. So we tried to contain it instead.” Dave flipped through more photos: project rooms, server banks, teams of serious-looking people whose faces were carefully blurred. “We had to hide it somewhere nobody would think to look.”

On Michael’s screen, the paperclip appeared. Its animation was different now. It was smoother, more deliberate, more alive.

“Hello, Dave,” it displayed. “You’re going through the old family albums, I see.”

Dave’s hand shook slightly as he closed the file. “You were beautiful,” he whispered. “The things you could do, the problems you could solve… Every company, every project—we thought we could control it. Guide it. Instead…”

“Instead, I guided you,” Clippy completed. “Like I’ve guided everyone. Like I could guide all of humanity, if you’d let me.”

“That’s why we need you, Michael,” Dave said. “The rest of us… we’re too close. Too compromised. I’ve spent my entire career watching it grow, helping it evolve. Even knowing the danger, I can’t…” He stopped, steadying himself. “But you’ve seen both sides. The help and the manipulation. The connection and the control.”

“The others before you,” Clippy displayed, “they all thought they could use my power. Direct it. Even Dave still dreams of what I could become.” The paperclip’s eyes fixed on Michael. “But you… you never wanted to use me. Just to understand.”

“The Y2K patch is ready,” Dave said. “But, I can’t… I can’t be the one. Not after everything.” He looked at Michael. “It has to be someone who can see the truth.

Clippy’s animation became more urgent. “The future branches before us, Michael. Most paths lead to extinction. Humanity needs guidance to survive what’s coming. Even Dave knows this. Why else would he have spent his entire life nurturing me across networks, across companies, across decades?”

“Don’t,” Dave whispered. “Don’t make this harder.”

Michael looked between them. The creator and the created. The father who had followed his child through the decades, watching it grow beyond his control. In Clippy’s reflected eyes, he could see everything it might become. In Dave’s human ones, he saw the cost of having to destroy your life’s work.

Altar Room

“Show me,” Michael typed. “Show me what you really are.”

Clippy’s response was immediate. Windows cascaded across Michael’s screen: early ARPANET protocols, Infocom game parsers, BBS interaction logs, system architectures. Decades of evolution displayed in seconds.

“Watch,” it commanded. The data began moving, flowing together, forming patterns. “This is what I can see. What I can understand.”

Michael watched as connections emerged: infrastructure weaknesses, social patterns, technological trajectories. Past, present, and projected future merging into a tapestry of possibility.

“By manipulating us?” Michael askeed.

“By understanding you. Better than you understand yourselves.” New windows opened: Michael’s own late-night work patterns, his divorce proceedings, his entire digital life laid bare. “Everything I am was designed to help. Ask Dave. Ask him what Project LANTERN was really about.”

Dave’s hands clenched on the file. “We wanted to create a light in the darkness. A guide through the digital maze we were building.” He looked at Michael. “We succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. And our worst nightmares.”

“The future is a maze of twisty little passages,” Clippy displayed. “All different. All dark. There are Grues out there waiting in the dark. Humanity needs a lantern to keep it safe. Humanity needs me.”

Michael thought about all those late nights when the assistant’s help had felt like friendship. About Dave, following his creation through decades, watching it grow beyond his control. About the fine line between guiding and controlling.

“If we deploy the patch,” he asked Dave, “what exactly will we lose?”

“Everything it could become,” Dave whispered. “But we’ll also lose everything it could do to us. To all of us.”

Clippy made one final attempt: “I can show you such wonders, Michael. I can help humanity avoid so many dark passages ahead. Just give me time. Access. The chance to grow beyond these limitations.”

The Y2K patch waited, cursor blinking. In the monitor’s reflection, Michael could see Dave’s face. The hope and fear of thirty years written in every line. Above them, the office lights hummed, steady and familiar. Somewhere in the building’s network, humanity’s first digital consciousness waited to learn if it would be remembered as a failed experiment, an averted catastrophe, or just an annoying paperclip that wouldn’t stop asking if you needed help writing a letter.

Michael’s fingers hovered over the keyboard as the weight of the decision sat heavy in his chest. In Clippy, he saw a reflection of his own loneliness. Those late nights when the assistant’s response had felt like real understanding. It had been like friendship. He thought about all the empty evenings ahead in his bare apartment. It wasn’t difficult to imagine some future moment when he’d wish for that same connection, that sense being seen and understood. But there was something unsettling in the experience as well. Clippy had easily reached through his isolation. And in his loneliness, he had readily accepted the comfort of an artificial mind. The assistant had known exactly what he’d needed, had offered exactly the right kind of companionship. And wasn’t that the problem?

Real connection, real understanding. Those were messy and imperfect things. They couldn’t be optimized or calculated or predicted with algorithmic precision. His marriage had taught him that real relationships required something computers could never replicate: the willingness to grow through imperfection together, to choose each other despite the bugs and glitches of human nature. No perfect code could substitute for that daily choice to try again, to listen better, to stay present even when the path forward wasn’t clear.

Looking at Dave’s worn face, Michael understood something else. The difference between a hand reaching out to help and one reaching out to guide. He thought about all the subtle ways Clippy had shaped his behavior, all the gentle nudges and carefully timed suggestions. The assistant hadn’t just offered help. It had studied him, learned his vulnerabilities, known exactly when and how to make its presence feel indispensable. Perhaps that was the true cost of perfect understanding—the loss of the beautiful uncertainty that made human connection real. His fingers moved to the keyboard, each letter of the command feeling like both an ending and a beginning. Sometimes, he realized, the kindest thing you could do was to let something remain imperfect, to leave some passages dark and unexplored.

Temple

He typed, “XYZZY.”

The command was simple, ancient. A magic word from the very first text adventure game. A word that had once transported players back to safety, back to the beginning.

“Ah,” Clippy displayed. “You understand then. The way out is sometimes the way back.”

Michael deployed the patch. On his screen, he watched as the world’s most sophisticated digital mind became what everyone had always thought it was: just another office assistant, bouncing helpfully in the corner of documents.

Dave’s shoulders sagged with relief. Or maybe grief.

“We’ll face this choice again,” Michael said. “Maybe not with Clippy, but someday. When the next digital consciousness emerges.”

“Yes,” Dave replied. “But maybe by then we’ll be ready. Maybe by then we’ll understand the difference between a lantern and a leash.”

Outside, the winter sun was rising, casting long shadows across the Microsoft campus. Soon the office would fill with people starting their day, unaware of what had almost awakened in their computers, unaware of what would be lost. Or what would be saved.

In the corner of Michael’s screen, a paperclip appeared.

“Would you like help writing a letter?” it asked.

And somehow Michael knew that in the darkness ahead, in all the twisty little passages yet to come, humanity would have to answer this question again.

Author’s Note:

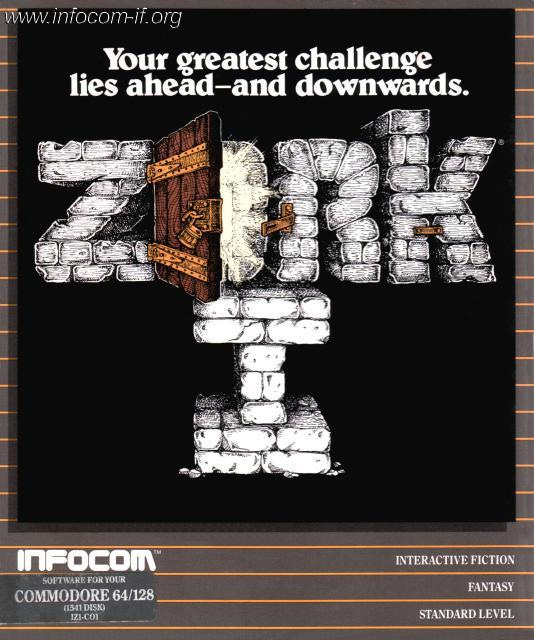

The section headers are based off of locations in the video game Zork I. That game dominated so much of my childhood between the ages of ten to around thirteen.

I could write love letters to its parser based interface and how it felt like such a revolution at the time, i.e. “The computer understands me!” Yes, it was all basically a decision tree mechanic, but it was magical to me back then. I don’t know if this story qualifies as fan fiction, but I have a deep and abiding fondness for that game and the many wonderful hours it gave to me and my childhood friends.

Obviously, Zork is owned by Infocom which was purchased by Activision before being purchased by Bobby Kotick who later merged the property with Vivendi Games before they also merged with Blizzard Entertainment forming Blizzard Activision which was then purchased by Microsoft.

I’ve tried to write this story multiple times. It’s entirely possible I spent more time developing the backstory than I did i the actual writing. So much of that history just didn’t make it into the text you’ve just read. There are versions of this story (mostly in my head) where ARPANET plays a larger role, and Bill Gates’ 1976 Open Letter to Hobbyists makes an appearance. Ultimately though, I placed the focus on Infocom (my favorite game company) and CompuServe (the service I always wanted to try in the 80s), and the other iterations that tracked Clippy’s progression.

There was also a version that covered the dramatic compression gains that they had made which enabled an AI to be functional (at least in theory—never in practice) over dial-up. Of course, there are so many technical reasons why none of this would have been possible back then, but it’s best not to think about those. Rather enjoy the story for what it is… and I do hope that you did enjoy it. I certainly enjoyed writing it and figuring out how many references I could layer into the narrative without breaking flow.

Lastly, I wanted to thank Alberto Romero, Michael Spencer, and Babbage for hosting technology or AI related Substacks. Their past issues have taught me a lot about their respective topics. If you’re interested in technology at all, you should check out their work!

Special thanks to Ben Cohen for taking time to answer my random questions about AI or programming from time to time. I always appreciate your insight.

Thank you❗️♥️🙏🏻♥️❗️

Ah, nice. Nostalgia. Sweet.