“It was my fault. I’m the one who killed our son.” I was disconsolate. I sat at the foot of the hospital bed questioning everything.

One of the monitors was still beeping. Leads that had been hooked up to my son’s chest just moments before now dangled from long cords. The sheets and bedding lay in a tangled mess.

My wife, Ashley, still stood in the doorway. The two steaming cups she held told me that she had successfully found her sought-after coffee.

I wasn’t sure she’d actually heard the words I’d said, but she did register Jimmy’s absence. The look of uncomprehending horror on her face told me that much. The last time I’d seen that look was when the doctors had given us Jimmy’s diagnosis.

Both cups of coffee dropped to the floor. Foaming sprays of steaming liquid covered the vinyl tile flooring of the small, stuffy room.

I started to rise. I wanted to go to her. To comfort her, but the look she gave me kept me in place. The comfort phase would come later. Right now, she had to deal with this initial shock on her own.

Now—just like when we’d received the initial diagnosis—none of the words I’d said were real to her. This was part of her process. First, denial, and then, the desperate fight to change reality. Dealing with impossible news was an emotional journey that we had made many times over the past three and a half years.

As with any repeated journey, you become familiar with the landmarks. That’s why it shocked me when Ashley rushed into the room. She bumped the child-sized table that held an unfinished puzzle Jimmy had been working on for weeks. Jigsaw pieces flew everywhere.

She collapsed on the floor and began to frantically dig through the small mountain of stuffed animals that had been gifted to Jimmy during his hospital stay.

When a child is dying, they get all the toys. That had certainly been true in Jimmy’s life. When a child is first diagnosed with cancer, the entire family shows up. Over time though, they reach a limit for how much sorrow they’re able to endure. So they stop coming and send plush toys instead. The stuffed animals are emissaries of sorrow. They are sent as proxy for the relative who can no longer endure the hollow-eyed stares of the afflicted.

Ashley still hadn’t spoken. She was so myopically focused on the toys that I wasn’t sure if she’d noticed that I was in the room. I didn’t want to rush her. She would speak when she was ready, but I could help her now.

I reached into the pile of animals and pulled out a stuffed bear. It wore a tuxedo and bow tie. The fur had been worn away in parts. It was my son’s favorite.

It was also the one I hated most. That was the plushie she sought. It was the one she had to find.

It was the cancer bear. Jimmy had taken that bear to every chemo treatment and doctor appointment he’d ever had. The bear had heard every whispered hope, every revised treatment plan, and all of what turned out to be false promises to which we were subjected over the years.

It had born mute witness to the many hours my wife had spent on her laptop. It saw her schedule appointments with other doctors, all the hours she spent reading about his diagnosis, and the endless research into alternate treatments.

I let her do all of that alone. At times, I felt guilty for not helping with the research, but I think part of me understood that the activity was how she dealt with the situation.

Her research led us to Sacred Heart Hospital. It was a small hospital in the Southeast, but they had a phenomenal track record when it came to childhood cancers.

The bear had given my son strength, but had only ever offered me a persistent reminder of all that we had lost. How could the doctors take my son and leave me this stupid bear?

My wife snatched the bear from my grasp. She clutched it tightly in her arms and turned away from me while she gave it a fierce hug. The bear’s lifeless brown eyes stared into my own.

Its eyes reminded me of the look of joy I’d seen fill my son’s eyes when I handed him the bear. It had been a bad day for all of us. The doctors had told us that Jimmy was stage four and had insisted that we start chemo right away.

Chemo meant needles and Jimmy hated needles. It still strikes me as funny that they’d just given the kid a death sentence and he was objecting to a shot.

The thing that infuriates me about that day was all of their statements. ‘We need to start chemo.’ The use of ‘we’ like it was a group effort, but Jimmy was the only one doing the heavy lifting. He was the one who had to deal with the nausea and later the radiation burns. Yet amid all of that suffering, he could still be touched by a last-minute gift. A present that I hadn’t even put any thought into. It was something I’d grabbed at the gift shop right before getting onto the elevator.

He clutched that bear to his chest. His small form was draped in a hospital gown that was a little too big. He lay in the bed because the medicine had made him too weak to do much else. For just a moment though that bear had made him smile. I had been able to gift him a few seconds of relief. Just a moment where he’d forgotten the tangle of IV lines and how the tape for the nasal cannula had irritated the skin on his smooth cheek. I’d happily trade another twenty bucks every day of the week to see him smile like that one more time.

Ashley sniffed the top of the bear’s head searching for some scent memory of our son. Then, still without speaking she stood and sat next to me on what had been Jimmy’s small bed. I placed an arm over her shoulder and she buried her face in my chest and began to cry.

A few hours earlier Jimmy had been laying in the bed. It had been a bad day. The chemo had made him particularly sick this time. He refused to eat. He couldn’t keep the liquid meals they shot into him through the feeding tube down. The nurse had argued with me about it, but I just wanted him to have a break. He’d suffered so much already. If he wanted respite from the nausea and vomiting I was going to see that he got it.

Jimmy’s treatments seemed to stretch on forever. Day after day filled with waiting. Waiting for scan results. Waiting to speak to a specialist. Waiting to find out if we’d been accepted into a new trial. Waiting for the chemo bag to drip its last drop into the veins of my dying son. If he wanted to wait for a meal, why was that such a bad thing?

The nurse kept pushing the issue though and I exploded. I shouted at her and had just started to develop a good head of steam to really let her have it when I felt my wife’s hand on my arm. I bit my tongue and stormed out of the room.

That was when I realized Jimmy was going to die. I couldn’t take it. I stepped away from the open door and quietly made my way down the hall. A few nuns nodded as they walked past me. I just kept walking.

I turned a corner and found an abandoned hallway. A large corkboard had been hung there. It was covered with the pictures of children who had received treatment at Sacred Heart. These children had not only lived, but appeared to have made full recoveries.

Dozens and dozens of smiling faces. Some of the children held hand-made signs that contained expressions of gratitude for the doctors or nurses that had provided care for them. The top of the bulletin board was covered with a hand-lettered sign that read Our Little Miracles.

I knew my son’s picture would never hang on that wall… and it broke me. I bit my lower lip. I’d hoped the pain would distract me. Force me to think about something different, but it didn’t work. I felt the beginnings of an anguished cry and clenched my teeth. I couldn’t let myself break down. Not here. Not this close to Ashley and Jimmy. I had to be strong for them.

It was pointless. I felt tears make their stinging escape. I wiped them away with a shirt sleeve. This was more of an effort to protect my delusional hope that everything was going to be okay rather than some misguided effort to preserve my dignity. When I thought I had everything under control, I started back to my son’s room. I’d barely made it two steps when my composure broke.

The agonized cry I’d tried to stifle escaped in a long wail. I didn’t cry so much as openly weep. It was one of those deep, sobbing cries most commonly associated with toddlers. The deep, ragged breaths. The shuttering fits and starts. Finally, all of my incoherent expressions of grief turned into a spoken question. Maybe even an indictment. “Why? Why does Jimmy have to go? Take me. Let my boy live. Let him live! Please God.”

Yes, I know. Clichéd. How many stories have featured the desperate parent pleading for the life of their child? Too many I’m sure, but the fact is that there’s a reason it’s a cliché. In those situations, it’s a natural response. I’d uttered the prayer—if you want to call it that—without even pausing to consider whether my actions were rational or not. The only thing I wanted at that moment was for my son to live.

Just then, I heard the wheel of a cart squeak as it rounded the corner down at the end of the hall. I dried my eyes as best I could and turned to face the sound.

Far at the end of that lonely corridor I saw the cart and its handler silhouetted against distant lights. Squeak. Squeak. Squeak. Slowly, but persistently, they made their way toward me.

It was late. The hospital’s electrical systems had automatically turned off every other fluorescent in an attempt to save energy. It filled the empty space of that corridor with long shadows and a sense of emptiness. I watched the cart’s progression as it drew nearer.

I didn’t want to engage in social nicities—not even for the seconds it took to nod hello as we passed one another. So, I pretended to be intrigued by the pictures of the many children who had been saved by the interventions of hospital staff.

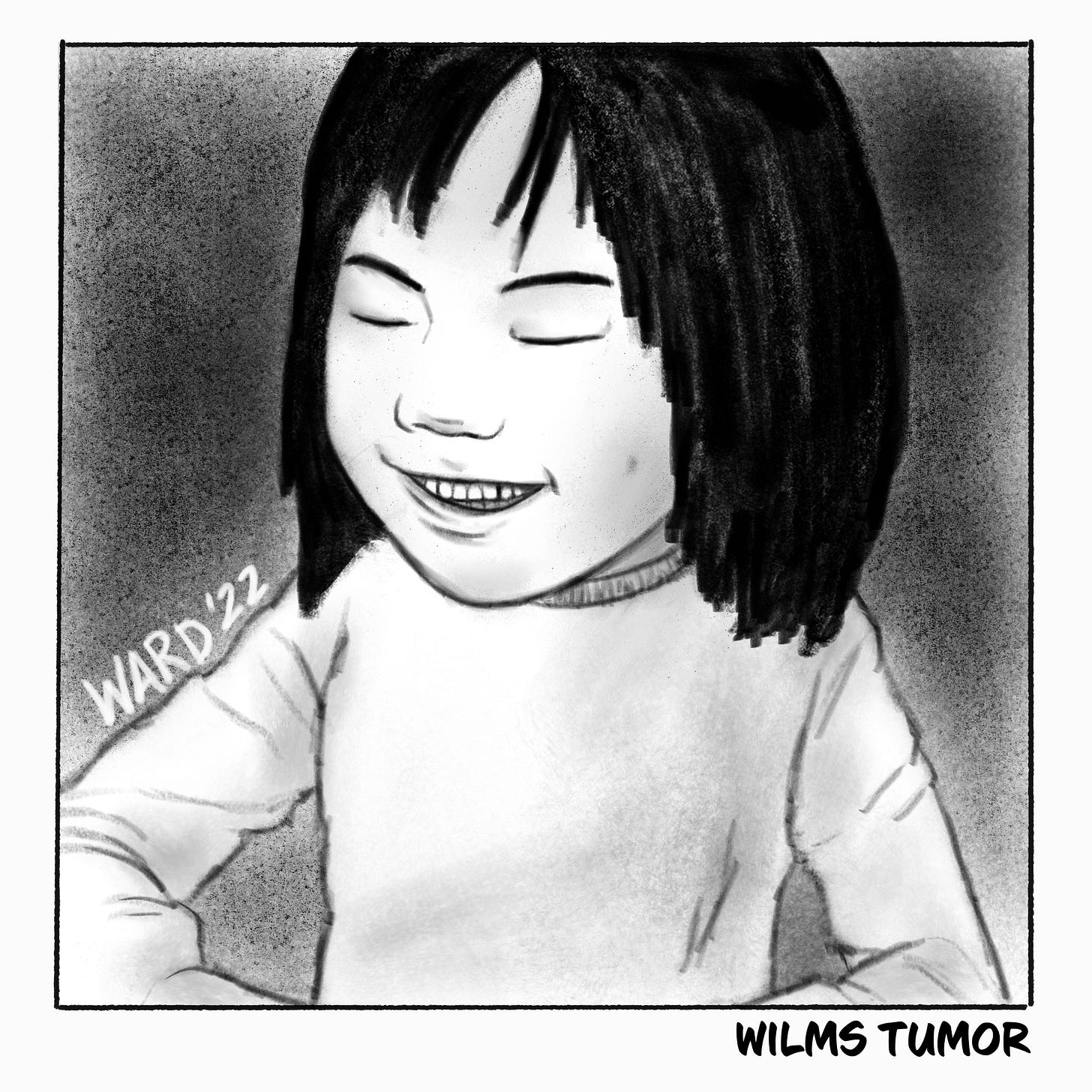

I bent closer to examine the picture of a small Asian girl who may have been four years old. At the bottom of the photograph were the words Wilms tumor. She radiated so much happiness. Her smile convinced me that she had made a full recovery.

The cart continued its relentless journey.

I looked at the picture to the right. A tall, lanky boy of around eleven. He held a basketball in the crook of his arm and an enormous smile that was full of hope for a future that had been doubtlessly denied him just years earlier. Under his picture was the word Rhabdomyosarcoma. I had no idea what that was, but it sounded horrible. Yet, here he was the very picture of health.

The next child was still an infant. Arms raised in that grasping motion all babies make. Swaddled in a blue blanket and wearing only a diaper, the child smiled at the camera in one of the most endearing displays of pure joy that I had ever seen.

Beneath the baby’s picture was the word Neuroblastoma. How did they treat cancer in someone so young? Yet, the baby had not only been healed, but seemed to be actively thriving.

The cart rattled to a stop behind me. I turned to see that it was a common janitorial cart. Its owner was swathed in shadow. He stepped into the light and I saw that he was a little below average height, slightly pudgy, and extremely old. He wore white coveralls that although they were clean had clearly seen better days.

His most striking feature, though, was his hair. It was as black as the shale I used to skip across the river when I was a boy. That memory made realize I’d never be able to do that with Jimmy and I had to fight back the tears all over again.

If the man noticed my tears, he didn’t mention them. Instead, he gave me an expansive smile and said, “The work they do here sure is something, ain’t it? I’m just tickled to be part of a place that helps people.”

I regarded the bulletin board one more time with thinning amounts of patience, “It’s incredible. I’ll give you that, but is it real though? Were these children really healed?”

“Oh yes! Indeed they were.” He said it with such conviction. “I’ve been here for decades and you won’t believe some of the turn-arounds I’ve seen.” He plucked the picture of the Asian girl off of the board. “That’s little Anh Bao. I remember her. So very, very sick when she came, but look at her now. All smiles! That’s the way childhood should be. All smiles!”

“Who was her doctor?” I demanded. The man didn’t answer and before I knew what I was doing I’d grabbed the front of his coveralls and balled the fabric into my fists. “Are they accepting new patients?”

The man met my outburst with a sense of equanimity that I found to be both surprising and unnerving. His smile never faltered. “You got a child here, mister? If so, you need to add their picture to the board.”

“The board? No. I need the right doctor. A different treatment. Something.” I shook him. “I need help, man! Can’t you see that? I need help.”

“And help is what I’m trying to give.” His smile went away as he looked down at my hands.

I let them drop to my sides. “I’m sorry. It’s just my son…”

He bent over his cart and moved some boxes to the side. From somewhere in the back, he pulled out a small object. “Hmm-hmm,” he said while nodding. “This is the help you need.”

I looked down at his offered gift. It was an old camera. A Polaroid. “Now, don’t you worry none. You put his picture up there and he’ll be just fine. This camera ain’t as fancy as your phone, but it’s easy to use. You just press that button on the top and the picture will come out here.” He pointed to a long slot at the base of the camera with his index finger. “When it comes out, you put that picture up on that bulletin board right away. Then, everything will be just fine.”

“Fine? Just fine? You haven’t even met my son. He’s dying! Don’t tell me he’s going to be fine.” I glanced at the collection of pictures on the wall. I wanted to rip them down. It felt like the faces of those smiling and healthy children were mocking both me and my son. I pointed at them and yelled, “I need help. Not some magical bulletin board…” The man was gone.

In his place lay the offered camera. I reached down and picked it up.

I returned to Jimmy’s room. He was still sleeping. We were alone. Ashley had doubtlessly stepped out to get a cup of coffee. She was predictable in some ways and one of her strongest routines was her coffee addiction. I smiled at the thought, but then my focus shifted back to our son.

He was so emaciated. He was completely bald. He’d lost so much weight that I could see the veins in his temple. There were yellow bruises on his arms in spots where they’d placed past IVs. My son had suffered so much.

I hated cancer. Hated it for Jimmy and for every person who had ever been afflicted by the terrible disease. I hated it for those who had been left behind.

An alarm chimed. At first, I thought it was the signal that it was time to change his IV bag. I’d have to call one of the nurses…

Jimmy’s body seized. The muscles in his arms and legs stiffened and his head pushed back into the mattress. Now, several alarms blared and then there was just one never-ending tone. I looked up at the heart monitor.

Jimmy had flat-lined.

Wasn’t this the time when dozens of doctors and nurses rushed into the room? That’s how it always happened in the movies. Just as I was getting ready to scream for help I heard the old man’s voice whisper, “You just press that button on the top and the picture will come out here.”

I can’t say whether I did it out of desperation or confusion, but I raised that black camera to eye level, found Jimmy in the viewfinder, and pressed the button. There was a whirring mechanical noise from inside the camera. A few seconds later, a square of white plastic emerged from the slot on the front.

I pulled it out of the camera and wondered where the picture of my son was, but as I watched portions began to darken and Jimmy’s form began to take shape in the image. Quickly, I ran to the bulletin board, grabbed one of the tacks that had been stuck into the cork board, and used it to put Jimmy’s picture in the empty space next to that of the Vietnamese child Anh Bao.

Several orderlies ran past me to Jimmy’s room. They wouldn’t let me back in, but I watched from the hallway as they tried to revive him time and again. They kept shocking him, but were unable to bring him back. Finally, a middle-aged man in scrubs came out and told me that my son had passed.

I wanted to ask a hundred questions, but I already knew the answers. I knew that I had been responsible for his death.

If I had called the doctors right away when that first alarm chimed they would have been able to save my son, but I’d been distracted by that old man’s foolishness and my desperate hope to make a difference.

I objected when they started to take Jimmy with them. My wife wasn’t here. She’d gone to get coffee and I knew that she would want to see him one more time. They explained that they would get him cleaned up and come get us so we could spend time with the body and that’s how I ended up sitting on the edge of Jimmy’s bed holding my wife and waiting for the doctors to tell us when we could see our son one last time.

There was a knock at the door. “Can’t you see…” I began. My tone was harsh, but my voice failed me when I saw who it was. The janitor had returned.

“I heard there was a spill in here and will you look at that? Probably half a pot of coffee right there on the floor. Let me just get my mop.” He stepped out of the room.

My wife’s shoulders heaved. She was sobbing uncontrollably now. I stroked her back. Just then, the janitor returned with a mop and a bucket. “Have to get this cleaned up before it dries. Sometimes if you get to a mess before it sets in you can still set everything right. Ain’t that right, Jimmy?”

Both my wife and I looked up and in the doorway stood our son. He was healthier than I’d seen him in years. He ran—he actually ran—into his mother’s arms and gave her a bear hug.

“What? How?” I stammered. Tears coursed down my cheeks. “Thank you.”

“You don’t have to thank me. The doctors’ll be by in a bit. I expect they’ll tell you about some kind of mechanical issue with their equipment or something. And that’ll be fine. Just let them think what they want to think, but do insist that they check out his tumor before they give Jimmy any more chemo or radiation. Make’em do another scan because Jimmy don’t need that stuff no more.”

Three weeks later we were discharged from the hospital. Jimmy’s scans showed that the tumor was no longer there. It was completely gone. No one could explain it. The discharge team came and wheeled Jimmy down to the elevators with his mom right by his side.

“Aren’t you coming?” she called back to me.

“Yes, I just have to do one more thing before we go.” I had stopped at the picture of Jimmy. It was so odd. I’d taken a picture of him while he was in the midst of some type of seizure or heart attack or I don’t know… but he was sprawled out on the bed. The picture that was on the wall showed him sitting next to that small table in his room with a completed puzzle covering the tabletop. He looked both happy and healthy.

I didn’t understand it, but I wasn’t going to ask any questions either. Instead, I pulled the marker from my pocket and wrote the word Glioblastoma under his picture and then raced to catch up to my family.

Heartbreaking. This is beautiful, thank you!

Made my heart race ♥️

Thank you for writing this powerful piece ♥️ With love ♥️